C.B. Bouton House

by: chicago designslinger

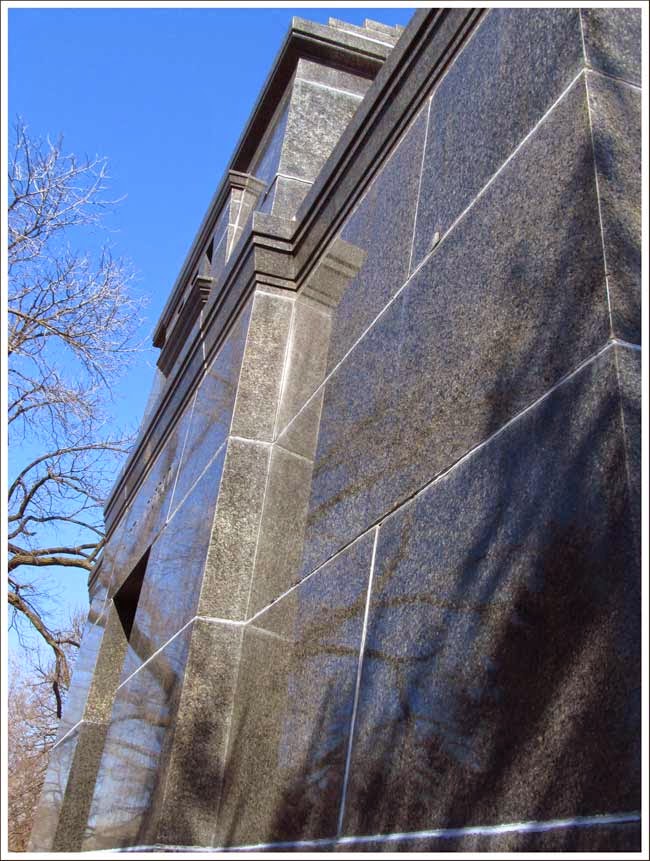

[C. B. Bouton House (1873) /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

The C.B. Bouton house is often identified as the C.S. Bouton house. But the person who built the Italianate style dwelling in 1873 - and lived there for the next 42 years - was Christopher Bell Bouton, son of Nathaniel and Mary A.P. Bell Bouton. Christopher, or C.B. as he was often referred to in contemporary publications, had an older brother Nathaniel Sherman Bouton, and may be the source of the misplaced middle initial. The two were also partners in a Chicago foundry business which may have added to the intializing error.

[C.B. Bouton House, 4812 S. Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

Their Union Foundry Works had gone through several name changes and partnership arrangements before Nathaniel incorporated the business in the early part of 1871 and was named president. His younger brother C.B. became the Secretary Treasurer. If you're familiar with Chicago history you probably know that something major happened in 1871 besides the Bouton brothers incorporating their business. The Union Works plant survived the Great Fire that October, but just barely. The inferno burned a few blocks from the foundry's location at 15th and Clark Streets, just beyond the southern edge of the burn district. The brothers lucked-out in more ways than one. When the rebuilding of the city began barely before the embers had cooled, wood was out and metal was in. Anything that could be done to prevent another catastrophic event like the one that had just happened from occurring again meant that the fire resistant cast iron that the Boutons produced would be an ideal building material in "fireproof" construction.

[C.B. Bouton House, Hyde Park - Kenwood National Historic District, Chicago /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

With business booming C.B. Bouton decided to build a house for he and his young family far outside the city limits in Hyde Park township, in an Arcadian area called Kenwood. He purchased a large piece of land, and in 1873 built a home in the very popular Italianate Style - the preferred style of men of means. Bouton's wife Ellenore Hoyt Bouton was the foundryman's third, his previous two marriages had ended with his other wives deaths. He met Ellenore through his brother Samuel who had married Ellenore's sister Mary Ann Hoyt in 1860, and in 1869, C.B. and Ellenore exchanged vows. In 1870 their son Sherman was born. Bertha was born in the Woodlawn Avenue house in 1874, followed by Mary in 1876, and Nathaniel on June 1, 1879, who died two months later.

[C.B. Bouton House, Kenwood Historic District, Chicago /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

Union Foundry continued to expand, not only providing architectural cast iron to a growing city, but the wheels and castings for the Pullman Palace Car Company and the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad. In 1886, at the relatively young age of 45, Bouton retired from the foundry business. Nathaniel was several years older than his younger brother and decided he'd had enough. Christopher and Ellenore purchased a winter home in Dunedin, Florida, and over time, the Bouton girls would each be married in the house on Woodlawn Avenue. In 1901, four years after his own marriage, young Sherman Bouton's funeral was held in the home. C.B. died in his large, Italianate-bracketed dwelling in 1915, forty-two years after moving in, at the age of 76.