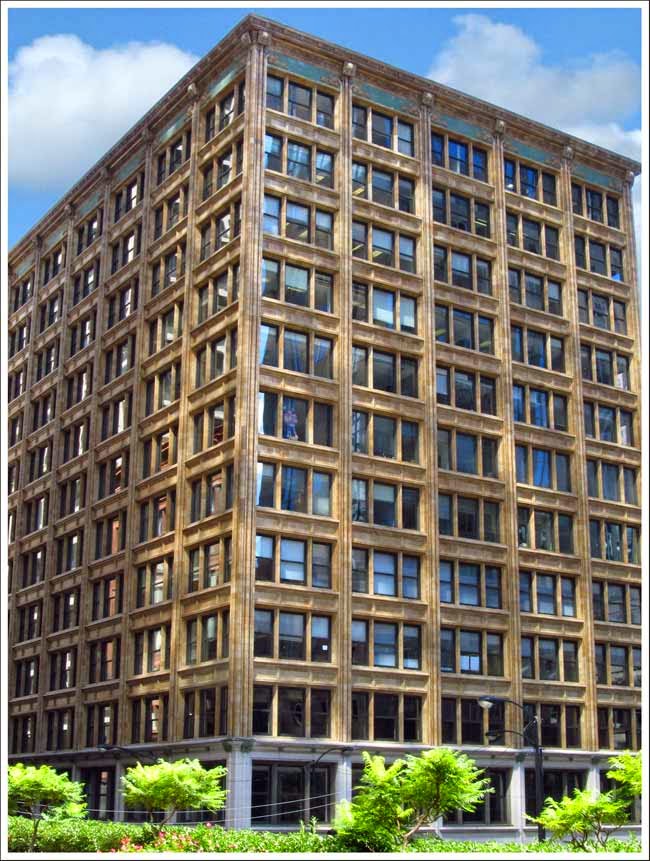

Brooks Building, Chicago

by: chicago designslinger

[Brooks Building (1910) Holabird & Roche, architects /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

If you didn't know to look, you'd probably miss Holabird & Roche's Brooks Building. Hidden in the long shadows cast by the 110 floors of Willis Tower and the 65 stories of the 311 S. Wacker Building - and not found in many popular architectural guide books or on tour routes - the diminutive 12 stories of the Brooks struggles to get a glimpse of the sun and much notice. But if you take a moment to pause at the intersection of Jackson and Franklin Streets you'll find one of the finest examples of the building style that made Chicago famous, which they helped create, and brought the 19th-century-era Chicago School of tall building design to a close.

[Brooks Building, 223 W. Jackson Boulevard, Chicago / Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

The building's name came from Boston's Peter and Shepherd Brooks. Taking a nice chunk of the fortune they'd inherited, the brothers started investing in the Chicago real estate market in the 1860s to help expand the size of their passed-down bank account. The brothers worked with a number of Chicago-based architects and most likely met William Holabird and Martin Roche in the mid-1880s through the architects former partner Ossian Simonds. Simonds was working with a Chicago investor named Bryan Lathrop on a plan for Graceland Cemetery, and Lathrop's brother-in-law just happened to be the Chicago agent for the New England-based financiers. It was an very profitable meet-up for all concerned. Holabrid & Roche virtually became the in-house architects for not only the Brookses, but also for Owen Aldis and Bryan Lathrop. By the time the designers were drawing up plans for the Brooks Building in 1908, William Holabird & Martin Roche had designed over a dozen buildings for the group, and this one bid adieu to the light, airy, wide-open-window building style that defined modern high-rise construction for a generation.

[Brooks Building, City of Chicago Landmark /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

In 1910 when the building was completed, the area around Jackson and Franklin was packed with loft-style warehouse buildings providing storage and manufacturing space to a city that produced and shipped millions of tons of goods and products from one side of the country to the other. And even though the building was built to serve as a light manufacturing and storage warehouse, the architects dressed-up the exterior with decorative terra-cotta glazed flourishes, minimally covering the underlying skeletal frame and leaving lots of room for wide expanses of glass. It was classic Chicago School, and the lightest and airiest looking structure in the entire warehouse district. And although the building sits in the shadow of its super-scaled neighbors today, it wasn't the first time the Brooks was sunblocked. From the time it was built until the summer of 1964, a steel super-structure supporting four elevated tracks of the Metropolitan West Side inter-urban rail line - later the CTA - sat three feet from the building's south wall. The tracks cut through what is now the middle section of 311 S. Wacker, crossed over Franklin, and ended one block east at Wells Street, giving the Brooks's lower floor tenants a close-up view of passing train cars.

[Brooks Building /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

The Brooks Estate sold the building in 1926, four years after Shepherd Brooks' death. But always on the look-out for positive cash flow, the Estate didn't sell the land along the with the building and leased the property to the new building owners for 198 years, garnering a rental income of $74,250 for the first five years and $81,000 a year for the remaining 193. As time marched on and the change that comes with it, the old warehouse district outlived its original purpose and many of its 19th-century and early 20th-century buildings were destroyed. But the Brooks survived, and was renovated, re-purposed, and converted into high-tech office space in 2001.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.