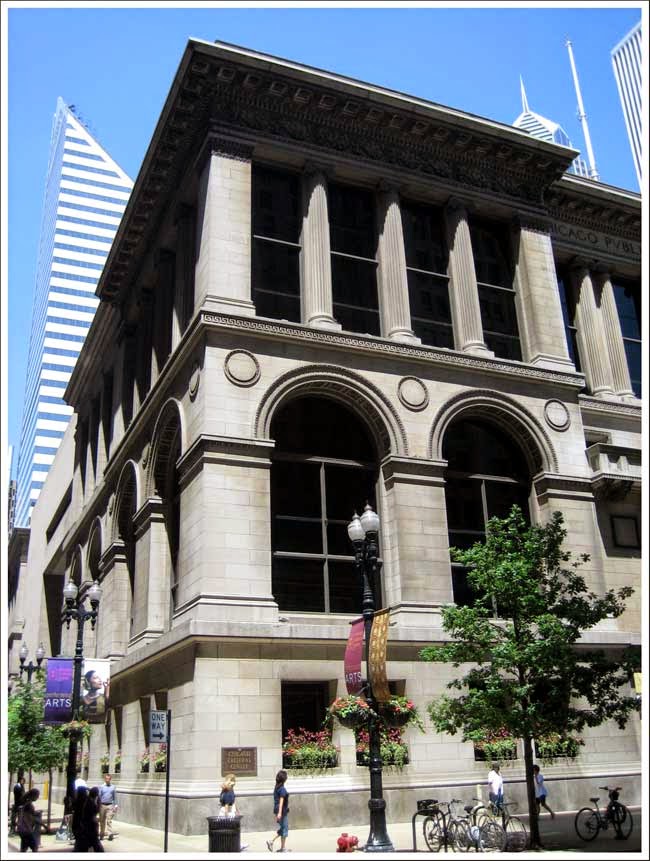

Chicago Cultural Center

by: chicago designslinger

[Chicago Cultural Center (1897) Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, architects; mosaics: Robert C. Spencer, Jr. designer, J.A. Holzer mosaicist, Tiffany Studios; art glass: Healy & Millet, Tiffany Studios; metal work: Winslow Brothers (2009) Tiffany dome restoration, Boffi Studio /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

When surveyor James Thompson drew-up a map and laid a grid over a river and a grassy plot of prairie land near the shore of Lake Michigan in 1830, the new town of Chicago's eastern boundary ended at the "Due North Line" - the western edge of the future State Street. The area from the North Line to the lake belonged to the federal government, and their Fort Dearborn Reservation didn't even get a mention on Thompson's plat. Nine years later, the feds decided they no longer needed the military outpost and deeded the property - which extended from the main branch of the Chicago River to today's Madison Street - to the city, who in turn, spread the grid out across the sandy land.

[Chicago Cultural Center, 78 E. Washington Street, Chicago /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

One small piece of land wasn't divided into salable lots, and a half-block section measuring 165 feet facing the lake, and 80 feet along Randolph and Washington Streets. The parcel became the only dedicated public space in the city - other than the grassy lawn around the Courthouse - and contained the notation, "Public Ground forever to remain vacant of Buildings." The map also marked-out a new street called Michigan Avenue, with its northern segment running from the main branch of the river south to Randolph Street. Michigan then ended as the shoreline of the lake inched-in toward what is today's curbline at the eastern edge of Michigan Avenue. The area around the park, with its refreshing lake breezes, became one of the city's poshest neighborhoods, located within easy walking distance of the nearby business district. Swept away by the fire in 1871, the former residential community was cut-off from the lakefront as fire debris was pushed into the water, extending the land area and pushing the lake shore further east. By 1883, commercial office buildings had completely overtaken the old settlers residential area and the City Council set their sights on the now forlorn looking piece of grass between Randolph and Washington.

[Chicago Cultural Center, National Register of Historic Places, Chicago /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

Chicago was no longer a podunk little cowpatch on the prairie, and a great city needed a great library. Chicago had a public library, but the books had never found a permanent home, and it was time to change that situation. The alderman passed an ordinance reinterpreting the vacant use of public ground to use for the public good, and proceeded with plans to build their library on the former Dearborn Park. Then Illinois' representative in the U.S. Senate, Civil War General John A. "Black Jack" Logan pushed a bill through Congress deeding the northern third of the park to the Soldiers Home of Chicago. The gossip on the street was that Logan, a staunch Republican, was trying to pull a fast one on Chicago's very popular mayor Carter H. Harrison, a devoted Democrat.

[Chicago Cultural Center, City of Chicago Landmark /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

In 1892 an agreement was reached between the city and the Soldier's Home - who acted on behalf of Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R) a Civil War veteran's group - to include a memorial hall and museum in the new building. The G.A.R. was given a 50 year lease on the space at a nominal fee (which was renewed in 1942 for another 50 years), and the Library Board invited 13 architectural firms to submit plans for a monumental building in the "Classical order of architecture." Boston architects Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge - who had just designed the new Art Institute building located two blocks south - won the prize. An entrance on Randolph Street led to the G.A.R. Hall, while the grand, Carrara marble-lined, mosaic glittering Washington Street staircase led into the glistening, Tiffany-domed, book Delivery Room. No one had seen such extensive mosaic work, and on such a scale, since the 12th century Cosmati glass tiling found at the Cathedral in Monreale, Italy - until Tiffany's mosaicist J.A. Holzer went to work in Chicago.

[Chicago Cultural Center, Historic Michigan Boulevard District, Chicago /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

By 1938 the library had already outgrown its space, and things came to a head in the late 1960s when the city couldn't delay the inevitable and decided that a new library building had to be built. Studies were commissioned on ways to save the old building while building new, but the plan simply wasn't feasible. And not everyone thought the 72-year-old structure was worth saving. 49th Ward Alderman Paul Wigoda believed that the structure was "not a first-class building," while Mayor Richard J. Daley's wife Eleanor was one of a number of people who thought differently. Not one to say much if anything in public, she let it be known that she thought the library was "beautiful and magnificent," and the building was saved from demolition. Today the structure that houses the Chicago Cultural Center no longer serves its original purpose, but it sparkles and is as packed with people as it was when it opened 115 years ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.