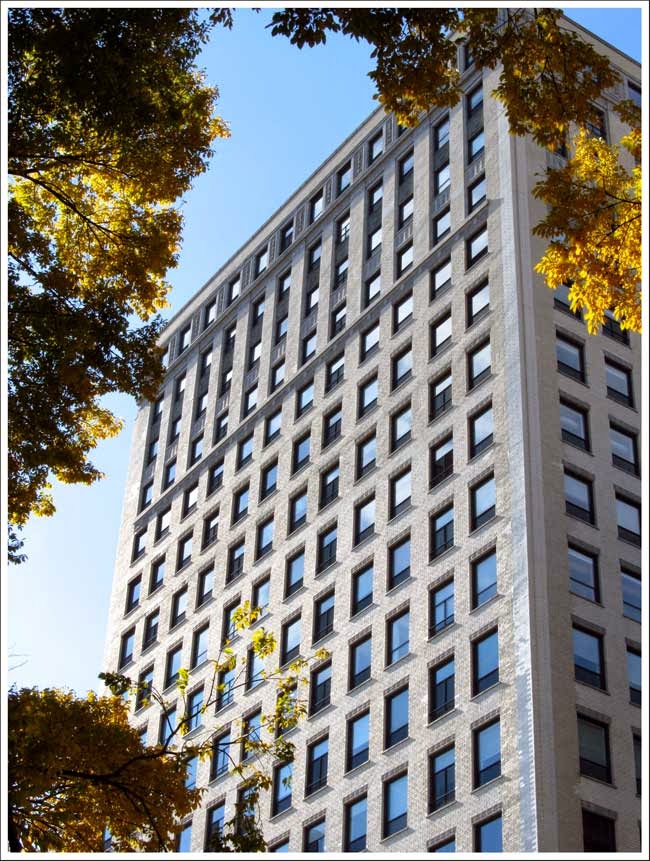

Michigan Avenue Lofts

Karpen & Standard Oil of Indiana Building

by: chicago designslinger

[Michigan Avenue Lofts - Karpen & Standard Oil of Indiana Building (1911) Marshall & Fox, architects (1927) addition, Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, architects /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

In 1880 a 22-year-old German-Jewish immigrant named Solomon Karpen took the $580 he had saved-up since arriving in Chicago eight years earlier and opened a furniture upholstery business. Solomon's father Moritz had been a cabinet maker in a part of Prussia that had once been Poland - and returned to being Poland after the First World War - and brought his wife and eight sons to Chicago hoping for a better life in the 19th century's version of the land of milk and honey. Upon his arrival in the U.S. in 1872, the oldest Karpen boy used the carpentry skills he had learned under his father's tutelage to find work in the Chicago's burgeoning furniture manufacturing industry. With his savings he opened S. Karpen & Bros., and as Solomon's younger siblings came of age the brothers portion of the company expanded along with the business.

[Michigan Avenue Lofts - Karpen & Standard Oil of Indiana Building, 910 S. Michigan Avenue, Chicago /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

When you're strolling down Michigan Avenue today past Chicago's Art Institute and the ever popular Millennium Park, it's hard to believe that when Karpen & Bros. moved into a shop and showroom on the lake-facing boulevard, the avenue was lined with loft manufacturing buildings that stood side-by-side with some of the city's more prestigious hotels. Their 6-story building on the west side of Michigan at Adams Street looked directly into the looming glass facade of the Interstate Exposition Building and was close to the city's bustling manufactured-goods-transporting train stations. The network of rail lines that converged at the center of the centrally located U.S. city turned Chicago into a manufacturing mecca, which in turn greatly improved the fortunes of Solomon and his brothers. But, as he wrote in a 1912 essay titled, How to Become A Millionaire, "No matter what money you have, don't allow it to be idle."

[Michigan Avenue Lofts - Karpen & Standard Oil of Indiana Building, Historic Michigan Boulevard District, Chicago /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

Solomon never allowed any monies invested in property to sit idle. He sold the Adams Street corner to the Peoples Gas Light & Coke Company for a tidy profit, bought the bankrupt Hotel Richelieu building just down the street for a song, and by the time he was able to realize a tidy profit from the sale of that building in 1910, S. Karpen & Bros. had become the largest upholstering and furniture manufacturing company in the world. For his next move Solomon took a long-term leasehold on a large corner lot at Michigan and Eldridge Court (today's 9th Street) for 99-years from the Otto Young estate. He had the architectural firm of Marshall & Fox draw-up plans for a 20-story building even though the furniture-making-mogul would only be building to a height of 13-stories, where the company occupied less than half of the space and rented-out the rest. In 1926, after 15 years of occupancy, even though Karpen Bros. had plenty of money in the bank, Solomon sold his 13-story, U-shaped structure to the Standard Oil Company of Indiana for $1 million more than he'd paid for it.

[Michigan Avenue Lofts - Karpen & Standard Oil of Indiana Building, Chicago /Image & Artwork: chicago designslinger]

In 1889 John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company established a 1,400-acre refinery in Whiting, Indiana adjacent to the Illinois border - which also just happened to be near the recently expanded border of the City of Chicago. Given the size of the Whiting refinery, the oil tycoon decided that Standard needed a regional office in the area and instead of choosing nearby Gary, Indiana he chose to go a little further up the Lake Michigan shoreline and opened offices in Chicago's bustling central business district. By the time Standard purchased the Karpen Building and the land underneath it from the Young estate in 1927, Rockefeller's Standard Oil trust had been broken-up into several subsidiary companies and Standard of Indiana had become one of the largest and most profitable of the regional outposts. The purchase of the building and land allowed Standard to consolidate their scattered Chicago offices into one building, and needing more space, they undertook the construction of the additional floors that Marshall & Fox's structural framing had planned for. Architects Graham, Anderson, Probst & White not only added a few more floors to the structure, they also incorporated a discreet "S" and "O" into the white terra-cotta heraldic panel near the top of the now 20-story building. By the late 60s Standard was ready for a new, modern, up-to-date, Chicago-centric headquarters and began construction on a new building at the north end of Grant Park. The aging Karpen & Bros. property sat vacant, was rented by the State of Illinois for a period of time in the 1980s, sat vacant again, and was converted into residential condominiums in the mid-1990s. It marked the beginnings of a long line of conversions that now stretch along the entire length Michigan Avenue's Grant Park-facing facades.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.